What’s the Difference Between Compensated vs. Decompensated Cirrhosis?

Cirrhosis can feel confusing, especially after a diagnosis. Doctors often describe it in two stages, and each stage affects daily life in different ways. This difference shapes symptoms, treatment plans, and future health.

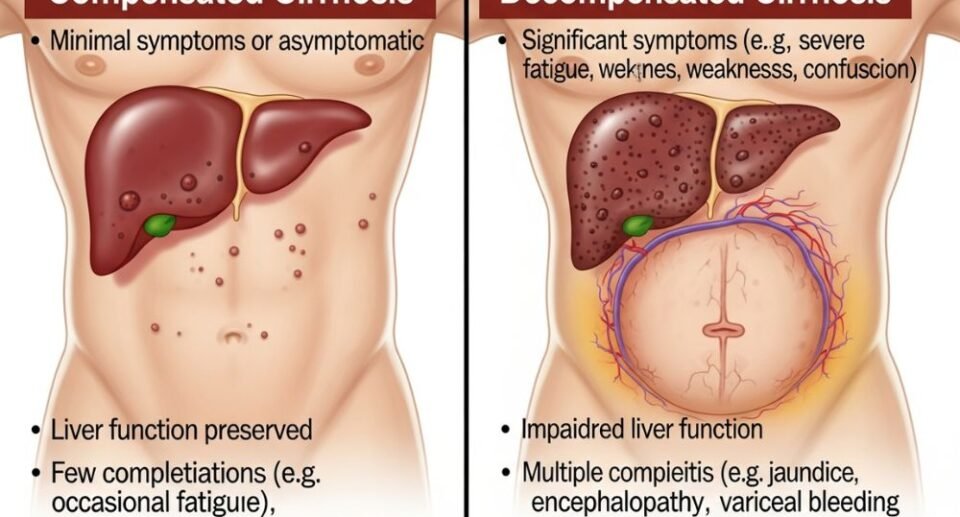

Compensated cirrhosis means the liver still performs most of its jobs, while decompensated cirrhosis means the liver no longer works well and causes serious problems. In the compensated stage, a person may feel mostly well because the liver adapts to damage. However, the decompensated stage brings visible signs such as fluid buildup, confusion, or yellow skin.

This article explains how these stages differ, what signs may appear, and how care changes over time. With a clear picture of each stage, it becomes easier to understand what doctors watch for and why early care matters.

Understanding Compensated vs. Decompensated Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis develops in stages that affect how well the liver works and how a person feels. These stages shape symptoms, risks, daily life, and expected survival.

Defining Cirrhosis and Its Stages

Cirrhosis describes permanent scarring that replaces healthy liver tissue over time. This scarring disrupts blood flow and limits the liver’s ability to perform basic tasks. Doctors group cirrhosis into two main stages based on liver performance.

In compensated cirrhosis, the liver adapts to damage and still performs most functions. Many people notice few or no symptoms at this stage. The body adjusts, and routine lab tests may show only mild changes.

Decompensated cirrhosis marks a shift in disease severity. The liver can no longer manage its workload. Problems such as fluid buildup, jaundice, or confusion appear. The term cirrhosis of the liver often applies to both stages, but the daily impact differs sharply.

Key Differences in Liver Function

The main difference between the two stages lies in how well the liver performs its important jobs. A compensated liver still processes toxins, produces proteins, and supports digestion. As a result, the person often maintains stable health.

Decompensated cirrhosis signals loss of this balance. The liver fails to clear waste from the blood. Protein production drops, which affects clotting and fluid control.

Common features that separate the stages include:

- Compensated: mild fatigue, appetite changes, few outward signs

- Decompensated: ascites, swelling in legs, yellow skin, mental changes

These changes reflect reduced liver reserve rather than sudden damage. Therefore, careful monitoring helps detect early shifts.

Progression From Compensation to Decompensation

Cirrhosis often worsens over time, although the pace varies. Ongoing injury from alcohol, viral hepatitis, or fatty liver disease speeds this shift. As scar tissue spreads, pressure rises in liver blood vessels and function declines.

Certain events push the liver past its limits. Infections, bleeding from enlarged veins, or missed treatment can trigger decompensation. Each episode places extra strain on the organ.

However, treatment can slow the decline. Alcohol avoidance, targeted medicines, and diet changes help protect remaining function. Regular follow-up allows doctors to address risks before severe symptoms appear. Early action often delays major complications.

Impact on Survival and Quality of Life

Life expectancy differs sharply between stages. People with compensated cirrhosis often live many years with steady care. They usually maintain work, social activity, and independence.

Decompensated cirrhosis shortens survival and reduces daily comfort. Frequent hospital visits become common. Symptoms such as fatigue, swelling, and confusion affect routine tasks.

Quality of life depends on symptom control and cause management. Some people qualify for liver transplant evaluation after decompensation. Others focus on symptom relief and stability.

Clear stage recognition helps guide care choices. It also sets realistic expectations for health, support needs, and long-term planning.

Symptoms, Causes, and Management of Both Stages

Compensated and decompensated liver cirrhosis differ in symptoms, risks, and care needs. These differences affect daily health, treatment choices, and long-term outcomes.

Symptoms of Compensated Cirrhosis

Compensated liver cirrhosis often causes mild or no clear symptoms. Many people feel generally well and keep normal daily routines. As a result, doctors often find this stage during tests for another issue.

Common compensated cirrhosis symptoms include fatigue, mild weight loss, nausea, and loss of appetite. Some people notice abdominal discomfort or weakness. These signs may come and go, which delays diagnosis.

Despite fewer symptoms, scar tissue and fibrosis already affect liver structure. Portal hypertension may exist without obvious signs. Varices may also form, even though bleeding has not occurred. Regular follow-up matters because silent changes can still raise the risk of liver failure or liver cancer.

Symptoms and Complications of Decompensated Cirrhosis

Decompensated liver cirrhosis causes clear and serious cirrhosis symptoms. The liver can no longer manage key tasks, which leads to visible problems.

Common features include jaundice, ascites, and leg edema. Ascites often causes abdominal swelling and discomfort. In addition, hepatic encephalopathy may cause confusion, sleep changes, or poor focus.

Bleeding from varices can occur due to high portal pressure. Variceal bleeding requires urgent care. Some people develop spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, an infection of ascitic fluid. These issues often lead to hospital care and signal advanced liver failure.

Common Causes and Risk Factors

Both stages share the same root causes. Long-term damage leads to fibrosis and scar tissue, which then progress to cirrhosis.

Key causes include viral hepatitis, especially chronic hepatitis C and hepatitis B. Alcohol consumption remains a major factor, particularly with alcohol-related liver disease. In addition, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, also called NAFLD, links closely to obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

Other risks include genetic conditions, autoimmune disease, and long-term toxin exposure. Continued injury increases portal vein pressure and speeds progression from compensated to decompensated cirrhosis.

Diagnosis and Treatment Approaches

Doctors diagnose cirrhosis through blood tests, ultrasound, and other imaging. Liver biopsy may confirm the stage in select cases. Screening also checks for hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein changes.

Treatment for cirrhosis focuses on the cause and the stage. Antivirals treat hepatitis B or C. Lifestyle changes and dietary changes address NAFLD and alcohol use. Beta-blockers lower portal hypertension and reduce bleeding risk.

Decompensated care targets complications. Paracentesis relieves ascites. Band ligation treats varices. Lactulose and rifaximin manage encephalopathy. Some patients need TIPS or evaluation for liver transplantation or a liver transplant.

Conclusion

Compensated cirrhosis means the liver still performs key tasks, while decompensated cirrhosis reflects clear loss of function and serious symptoms.

People with compensated disease often feel few effects; however, decompensated disease brings problems such as jaundice, fluid buildup, and confusion.

As a result, care shifts from routine checks and cause control to active treatment of complications and transplant review.

Clear knowledge of both stages helps patients and clinicians discuss risks, timelines, and next steps with confidence.